Tagar #KaburAjaDulu Viral, Anak Muda Curhat Tekanan Hidup di Media Sosial

Jakarta – Tagar #KaburAjaDulu mendadak viral di berbagai platform media sosial dan menjadi bahan perbincangan luas warganet Indonesia. Tagar ini digunakan oleh banyak anak muda untuk mengekspresikan keinginan “menjauh sejenak”…

Read moreFilm Lokal Tembus Jutaan Penonton, Industri Perfilman Indonesia Kian Bergairah

Jakarta – Industri perfilman Tanah Air kembali menunjukkan tren positif setelah sebuah film Indonesia terbaru berhasil menembus angka jutaan penonton hanya dalam hitungan hari sejak penayangan perdananya di bioskop. Capaian…

Read moreTimnas Indonesia Bersiap Hadapi Laga Krusial, Antusias Suporter Memuncak

Jakarta – Timnas Indonesia tengah mematangkan persiapan jelang laga krusial dalam lanjutan kualifikasi turnamen internasional. Latihan intensif digelar di Jakarta dengan fokus pada peningkatan fisik, transisi permainan, dan penyelesaian akhir.…

Read moreLonjakan Penipuan Deepfake AI, Pemerintah Imbau Masyarakat Lebih Waspada

Jakarta – Pemerintah mengingatkan masyarakat untuk meningkatkan kewaspadaan terhadap penipuan berbasis kecerdasan buatan (AI) yang memanfaatkan teknologi deepfake. Dalam beberapa hari terakhir, beredar luas video dan pesan suara palsu yang…

Read moreKenaikan Harga BBM Non-Subsidi Picu Reaksi Publik dan Pelaku Usaha

Jakarta – Pemerintah resmi menyesuaikan harga BBM non-subsidi di sejumlah wilayah Indonesia mulai pekan ini. Kebijakan tersebut langsung memicu beragam reaksi dari masyarakat dan pelaku usaha, terutama di sektor transportasi…

Read moreGempa Magnitudo 6,1 Guncang Jawa Barat, Warga Sempat Panik

Bandung – Gempa bumi berkekuatan magnitudo 6,1 mengguncang sejumlah wilayah di Jawa Barat pada Minggu pagi. Getaran dirasakan cukup kuat di Bandung, Garut, Tasikmalaya, hingga sebagian wilayah Jabodetabek, sehingga membuat…

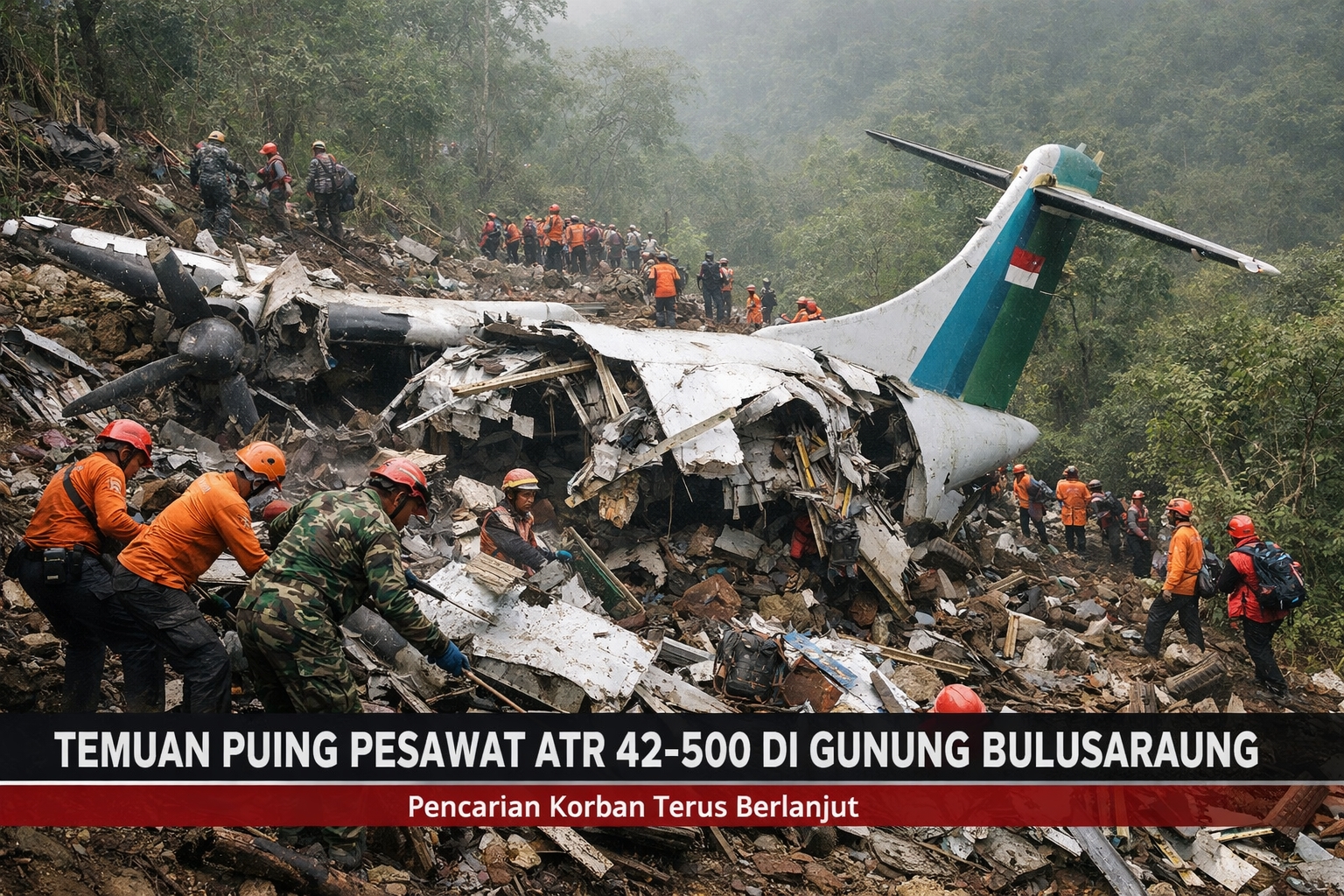

Read moreTemuan Puing Pesawat ATR 42-500 di Gunung Bulusaraung, Pencarian Korban Terus Berlanjut

Makassar, 18 Januari 2026 – Tim pencarian dan pertolongan (SAR) gabungan berhasil menemukan puing-puing pesawat turboprop ATR 42-500 yang hilang kontak saat terbang dari Yogyakarta menuju Makassar pada 17 Januari…

Read moreFISIP UPN “Veteran” Jakarta Hosts Seminar on Gender and Politics

Jakarta, October 29, 2025 – The Faculty of Social and Political Sciences (FISIP) at Universitas Pembangunan Nasional “Veteran” Jakarta once again organized a Seminar titled “Gender and Politics” on Wednesday,…

Read more Tagar #KaburAjaDulu Viral, Anak Muda Curhat Tekanan Hidup di Media Sosial

Tagar #KaburAjaDulu Viral, Anak Muda Curhat Tekanan Hidup di Media Sosial Film Lokal Tembus Jutaan Penonton, Industri Perfilman Indonesia Kian Bergairah

Film Lokal Tembus Jutaan Penonton, Industri Perfilman Indonesia Kian Bergairah Timnas Indonesia Bersiap Hadapi Laga Krusial, Antusias Suporter Memuncak

Timnas Indonesia Bersiap Hadapi Laga Krusial, Antusias Suporter Memuncak Lonjakan Penipuan Deepfake AI, Pemerintah Imbau Masyarakat Lebih Waspada

Lonjakan Penipuan Deepfake AI, Pemerintah Imbau Masyarakat Lebih Waspada Kenaikan Harga BBM Non-Subsidi Picu Reaksi Publik dan Pelaku Usaha

Kenaikan Harga BBM Non-Subsidi Picu Reaksi Publik dan Pelaku Usaha Gempa Magnitudo 6,1 Guncang Jawa Barat, Warga Sempat Panik

Gempa Magnitudo 6,1 Guncang Jawa Barat, Warga Sempat Panik Temuan Puing Pesawat ATR 42-500 di Gunung Bulusaraung, Pencarian Korban Terus Berlanjut

Temuan Puing Pesawat ATR 42-500 di Gunung Bulusaraung, Pencarian Korban Terus Berlanjut FISIP UPN “Veteran” Jakarta Hosts Seminar on Gender and Politics

FISIP UPN “Veteran” Jakarta Hosts Seminar on Gender and Politics